(image is from @images_ai)

Note how acoustic those AI 'paintings' are, echoing McLuhan's insight that electronic media are acoustic. They feel like a synaesthetic blend of musical motifs rather than strictly visual translations of the ideas described. They also overheat in overpoasting to create *cringe*.

— Duncan Reyburn (@duncanreyburn) December 7, 2021

My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless was the album of the 90s. Shoegaze is the genre of our time. That is because it is profoundly acoustic. If we look at Loveless’ Pitchfork’d neighbor, standing now one step down from the “Greatest Album of the 90s,” we see OK Computer, an artifice borne of visual culture.

McLuhan argued that the phonetic alphabet collapsed our senses into the visual realm, translating the simultaneity of sound into abstract representations. Rather than receiving the word in the river of sound we’re constantly immersed in, we can represent it as letters to our eyes and imagine it in our minds. To him, this collapse to the visual made our culture one of stark categories and abstract reasoning. McLuhan is most famous for his claims that “new media” — radio, television, and any medium made possible by electric technology — is not visual but acoustic or “primitive”. This media, in inspiring a passive and simultaneous state of reception, is regressive (and he, like I, would not use this term with its typical negative association).

In The Gutenberg Galaxy, he writes “Those who experience the first onset of a new technology, whether it be alphabet or radio, respond most emphatically beause the new sense ratios set up at once by the technological dilation of eye or ear, present men with a surprising new world, which evokes a vigorous new “closure,” or novel pattern of interplay, among all of the senses together. But the initial shock gradually dissipates as the entire community absorbs the new habit of perception into all of its areas of work and association.”

In OK Computer are the anthems of a visual culture in shock; Loveless is the chanting following the dissipation. Each song on OKC, pristine and shining, are three guitars, a bass, the drum tracks, Thom and harmony, synths, and various overdubs. They work in harmony, mixed expertly, but are distinct, as is characteristic of the art of a visual culture. Each song has a linearity to it, a storyline carrying it from intros through its choruses to outros, and a broader structure that plays out over the course of the album’s runtime. Thom sings alone over the instrumentals implicitly or explicitly about modern alienation. “OK, computers,” with wide-eyes as the new technology batters the senses.

Loveless’ arrangements blur the distinction between any of the myriad guitars, between any of the unison voices. A bending wail sitting in the back of the mix may be the harmonics of the fuzzed out chords at the front of the mix, or it may be an overdub. This very tendency to attempt to “pick out” the individual parts is that of a visual mind, the examining mind poring over a text or driving a car. One listens to Loveless for its texture, a term critics often apply to the particular appeal of shoegaze, which refers to its simultaneity, like standing ear-deep in a rushing river. Texture is an analogy toward the sense of touch, a sense far less granular than our sight.

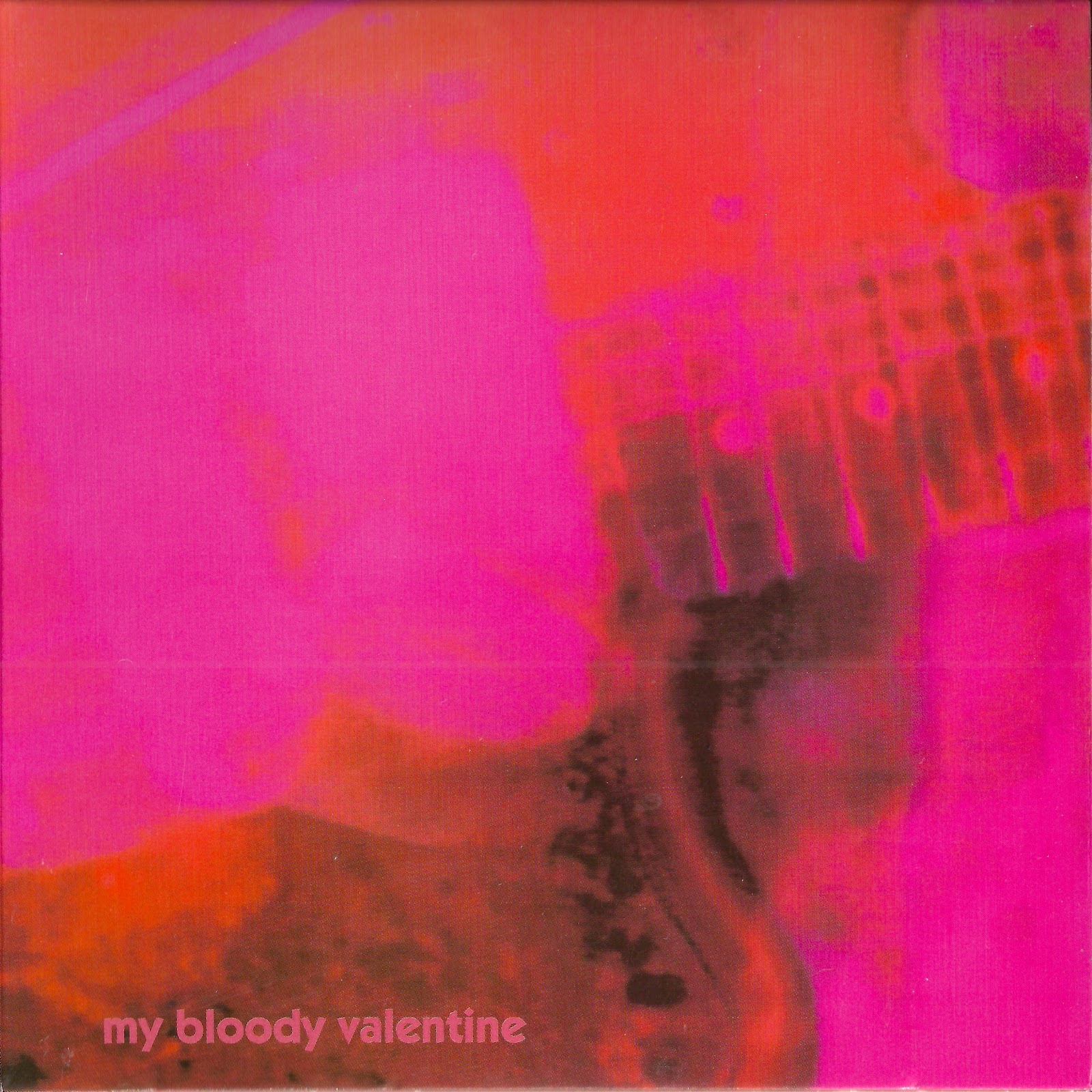

The cover of the album (an influence on the aesthetic of the site I’m not afraid to wear on my sleeve) seems to presage the mushy AI/ML paintings generated from human queries. The algorithm creates some amalgam of images more or less related to the query given. This amalgam is characteristically impossible to “parse” in the sense-making way we’ve evolved to. It is itself a texture, evoking something that has little to do with the intentional placement of its atoms in categories and scenes, as in the visual artifice.

Radiohead tried to catch up with Kid A, a far more fuzzy record. The timbres of voice and instrument often blend, it’s not nearly so distinct — yet equally as often they don’t, so the distinction between parts remains and the whole band can be imagined quite easily in the visual field. This makes it schizophrenic, back and forth between the visual and acoustic modes of sense, between immersion within simultaneity and distance by abstraction.

This same AI/ML technology can do music. It’s as you would expect: The Beatles generated by OpenAI Jukebox. The guitars are legion, the voices indescribable (Lennon or McCartney?), the words a mush. The whole thing is mushy like the paintings the technology generates. Where is this heading? One can only imagine that the many hidden weights will be gently coerced by the scientists toward the categories of music we are used to, but I imagine it will approach but never reach true imitation. The mushiness will always be beyond what humans so visually biased can stomach. The acoustics of these demons will be forever too haunting.